When a component fails, the first instinct is often to question the design. While design flaws do occur, many failures originate earlier or later in the lifecycle—during manufacturing, assembly, handling, or test. Identifying process-induced failures early helps teams avoid misdirected redesign efforts and focus corrective action where it will be most effective.

Recognizing these indicators early in a failure analysis can significantly reduce investigation time and prevent unnecessary design changes.

What Is a Process-Induced Failure?

A process-induced failure results from how a component was manufactured, assembled, handled, or tested rather than from an inherent design weakness. These failures often appear sporadic, inconsistent, or localized, making them easy to misclassify without careful analysis.

Standards organizations such as JEDEC and IPC emphasize separating design intent from process execution when evaluating failures

Indicator 1: Inconsistent Failure Location or Mode

Design-related failures tend to be repeatable and predictable. When failures appear in different locations or manifest in varying ways across otherwise identical parts, process variability becomes a strong suspect.

Examples include:

- Cracks appearing in different package regions

- Electrical opens occurring on different pins

- Intermittent failures with no consistent stress trigger

Such inconsistency often points to variation in assembly, handling, or test conditions rather than a systemic design flaw.

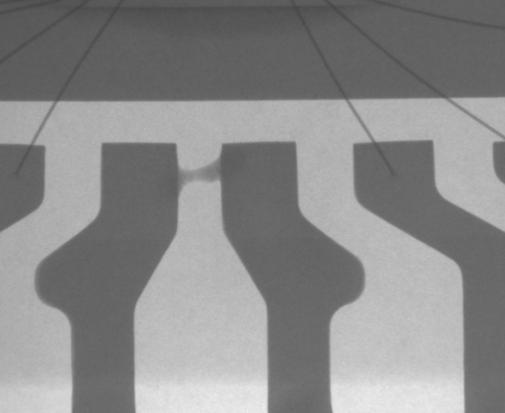

Indicator 2: Evidence of Localized Mechanical or Thermal Stress

Process-induced damage frequently leaves localized physical signatures. These may include bent leads, package cracking, bond wire deformation, or delamination confined to specific regions.

IPC guidance notes that excessive thermal cycling, improper reflow profiles, or mechanical loading during handling can introduce damage without immediately causing functional failure.

When stress indicators are localized rather than uniform, the likelihood of a process-related root cause increases.

Indicator 3: Failures Cluster Around Manufacturing or Test Steps

Another strong indicator is failure clustering around a specific process step. Examples include:

- Failures appearing after board assembly but not at incoming inspection

- Increased fallout following environmental or burn-in testing

- Issues isolated to a particular manufacturing lot or date range

NASA failure analysis guidance highlights the importance of correlating failures to lifecycle events rather than assuming intrinsic design weakness.

Temporal or process-step correlation is often one of the most powerful tools in distinguishing process-induced failures.

Indicator 4: Damage Inconsistent With Electrical Overstress

Electrical overstress (EOS) and electrostatic discharge (ESD) leave characteristic damage signatures. When observed damage does not match these patterns, process-related causes should be considered.

Examples include:

- Mechanical fractures without associated melt damage

- Corrosion without evidence of electrical overstress

- Partial interconnect damage inconsistent with current flow

JEDEC documentation outlines typical EOS and ESD signatures, providing useful comparison points during analysis.

Mismatch between observed damage and expected electrical failure modes often redirects the investigation toward process conditions.

Indicator 5: Known-Good Designs With New Failure Behavior

When a design has an established field history or qualification pedigree, sudden failure emergence is rarely design-driven. Changes in suppliers, materials, assembly processes, or test conditions are more likely contributors.

In these cases, confirming what changed in the process often yields faster insight than reevaluating the design itself.

Why Early Classification Matters

Misclassifying a process-induced failure as a design issue can lead to:

- Unnecessary redesign efforts

- Increased cost and schedule delays

- Failure to address the true root cause

Early identification allows teams to focus corrective action on manufacturing controls, handling procedures, or test limits rather than altering otherwise sound designs.

Using Indicators Together

No single indicator is definitive on its own. However, when multiple indicators point toward process involvement, confidence increases significantly. Effective failure analysis evaluates electrical results, physical evidence, and process context together.

This integrated approach supports conclusions that are technically sound and defensible.

Learn more about our Failure Analysis and Engineering Services to see how process-induced failures are identified and addressed.

If you are facing unexplained failures and need help determining whether the issue is design- or process-related, contact Priority Labs to discuss your investigation needs.